Picture of the Statue of Liberty Picture of the Museum of Modern Art in New York

Check out the superlative 25 sculptures at MoMA

Have our tour of the works at the Museum of Modern Fine art that wrote the volume on mod and gimmicky art in 3-D

The Museum of Modernistic Art has one of the earth's greatest collections of 20th- and 21st-century paintings, and the same holds true of its holdings in sculpture. Granted, you can observe versions of some of the same objects in other institutions; sculptures, later all, can be cast or fabricated every bit multiples. But what is unique about MoMA is the context it creates thanks to the atypical role it has played in the shaping of Modernistic Art. No i tells the story better or in greater depth, which makes looking at a Brancusi there a whole other feel from seeing a similar one in another museum. MoMA provides the bigger picture, which makes all the departure. In that location are, in any instance, many more objects to behold that are unique, but the truth is, whether you lot're talking about an edition piece or not, there's probably way too much stuff to accept in. To remedy that, nosotros offering this handy guide to the 25 top sculptures at MoMA.

RECOMMENDED: The full guide to the Museum of Modern Art

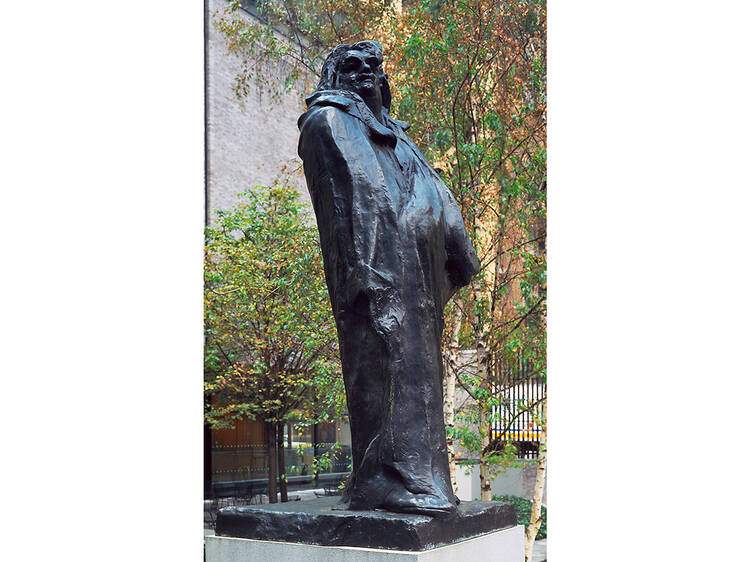

Auguste Rodin, Monument to Balzac (1898)

Rodin (1840–1917) won the commission for this homage to novelist Honoré de Balzac afterward the artist originally selected for the project—the neoclassicist Henri Chapu (1833–1891)—died before work could progress. Sponsored by France's Société des Gens de Lettres in 1891, the sculpture was supposed to take 18 months to consummate. Nonetheless, Rodin, taking a kind of method-acting arroyo, immersed himself in the life and piece of work of his subject. Instead of 18 months, it took Rodin seven years and fifty unlike studies (besides equally side trips to the Balzac's hometown, and asking Balzac's tailor to replicate the writer'due south apparel) to deliver a full-size plaster maquette. Most immediately, it was roundly castigated past critics and rejected past the Société for being too radical. It's piece of cake to encounter why: Balzac is depicted as an abstracted column with only his head visible to a higher place a cloak representing the 1 he wrapped himself in while writing. Defending himself against the naysayers, Rodin insisted his aim was to capture Balzac's persona, non his likeness, which may account for the fact that the first bronze of the piece wasn't struck until 1939—22 years later the artist's expiry.

Marcel Duchamp, Bike Bike (1913)

Bicycle Wheel is considered the kickoff of Duchamp'south revolutionary readymades, except that when he completed the piece in his Paris studio, he really had no idea what to telephone call it. "I had the happy thought to fasten a bicycle cycle to a kitchen stool and watch it plough," Duchamp would later on say. It took a 1915 trip to New York, and exposure to the city'south vast output of factory-built goods, for Duchamp to come up with the readymade term. More than importantly, he began to come across that making art in the traditional, handcrafted manner seemed pointless in the Industrial Historic period. Why carp, he posited, when widely available manufactured items could do the job. Afterwards all, it was the idea behind the artwork that was important, non how it was made. This notion—perhaps the showtime real case of Conceptual Fine art—would utterly transform art history going forward. Much like an ordinary household object, nevertheless, the original Bicycle Bike didn't survive: This version is actually a replica dating from 1951.

Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913)

Boccioni (1882–1916) was one of the principal theorists of Italian Futurism, peradventure the most controversial and unpredictable of the early modern movements. The Futurists celebrated the revolutionary furor and breakneck technological pace of the nascent 20th century, embracing its contradictions and frequent descents into violence. Even so, in the early going, artists like Boccioni remained beholden to the stylistic tropes of 19th-century Postimpressionism, peculiarly the Italian variant called Divisionism. A joint visit to Paris in 1911, however, provided an introduction to Cubism, and a way for the Futurists to make their work seem every bit radical equally their writings. They borrowed elements from Cubism's planar geometry, overlapping and repeating angular shapes to convey movement and speed. However, Boccioni, who'd been inspired by the Paris trip to carelessness painting for sculpture, began working in iii-dimensions, molding these concept into objects, similar this striding figure, which represents the spatial dynamics of the body in movement. By making the body armless, Boccioni directs the viewer'south attention to the sculpture's powerful legs, which seem to flap against the forcefulness of time and space.

Pablo Picasso, Guitar (1914)

In 1912, Picasso created a cardboard maquette of a piece that would have an outsized impact on 20th-century art. Besides in MoMA's collection, it depicted a guitar, a subject Picasso oft explored in painting and collage, and in many respects, Guitar transferred collage's cutting and paste techniques from 2 dimensions to 3. It did the same for Cubism, likewise, by assembling flat shapes to create a multifaceted form with both depth and volume. Picasso's innovation was to eschew the conventional carving and modeling of a sculpture out of a solid mass. Instead, Guitar was attached together like a construction. This idea would reflect from Russian Constructivism down to Minimalism and across. Two years after making the Guitar in cardboard, Picasso created this version in snipped can.

Constantin Brancusi, Bird in Space (1928)

An icon of Modern Art, Brancusi'southward Bird in Infinite was actually created as a series of 16 sculptures—seven in marble, nine in bronze. 2 of the latter are in MoMA's drove, including this highly polished version. The sculpture is more of a evocation of flying than an depiction of a bird: It's sleek configuration, which tapers and bulges before tapering again, is devoid of wings or anything else that is recognizable, and it'southward sleekness is characteristic of Brancusi's tendency to pare things down to their bare essence.

Meret Oppenheim, Object (1936)

Too known equally the fur-lined teacup, Oppenheim'south Object has one of the more interesting, if possibly apocryphal, backstories in modernistic art. It began with a chat at a Parisian café between Oppenheim, Picasso and Dora Maar, Picasso'due south lover and muse at the time. Admiring a fur-covered bracelet adorning Oppenheim's wrist, Picasso noted that anything could exist covered with fur, to which Oppenheim, pointing at her tea, supposedly replied, "Even this cup and saucer." Other versions of the story take her making a joke at a waiter'south expense, by asking for "more than fur" to warm upwards her potable, and earlier rushing out to a store to purchase the loving cup, saucer and spoon that makes up the work. What is clear, however, is that afterward André Breton, Surrealism's capo, asked Oppenheim to participate in an exhibition he was organizing, she submitted Object, which immediately became a sensation. Though it remains a Surrealist icon to this twenty-four hour period, Oppenheim never intended the many psychosexual interpretations ascribed to the piece. Instead, Object is a study in juxtaposing materials of contrary qualities—the warm and soft of fur with the common cold and hard of ceramic and metallic.

Alberto Giacometti, The Chariot (1950)

An statement could be made that other Giacomettis in MoMA'south holdings have a better merits to be on this list: His Surrealist tableau, The Palace at 4 a.thou., for example, or i of the earlier attenuated figures marking his postwar, existentialist phase. The Chariot fits into the latter, just is arguably unique because its large wheels (inspired by an orderly's cart the artist noticed during a cursory infirmary stay) prepare a dialogue between stasis—sculpture's "natural" state—and mobility. The field of study riding The Chariot is likewise a woman, and while Giacometti himself stated that he was primarily interested in creating a study of a figure suspended in space, the piece tin be read in retrospect equally an image of female empowerment. Some accounts claim a connection between the work and the creative person's mother, who was said to have been domineering. Such psychoanalytical assertions are e'er hard to show, but whatever y'all can say most The Chariot's importance, notation that a version of information technology did fetch $101 meg at auction in 2014.

Ellsworth Kelly, Sculpture for a Large Wall (1956–57)

A prime case of midcentury aesthetics and the corporate adoption of Modernism following World War Ii, this screenlike relief was originally made for the foyer of the Transportation Building in Philadelphia. Designed by builder Vincent Kling, the building itself—a hulking concrete construction—was role of a larger urban renewal project called Penn Center, one of many such undertakings in American cities that eventually eroded the conventionalities that modernism could abate social ills. In 1998, the building was reconstructed, requiring the removal of Kelly'south frieze from its place above the lobby'south elevator banks; that same yr MoMA, acquired information technology for its collection. Measuring some eleven by 65 feet, Kelly'due south piece consists of four horizontal rows of widely spaced, anodized aluminum panels cut into roughly trapezoidal shapes, some with 1 side curved in a concave or convex line. Many of the panels are covered in a single colour—red, bluish, blackness, gilded, bronze or gray, though most are sliver—and bending in and out from the sculpture'due south armature: Iv long rods, running parallel to one another along the length of the piece. These variations gear up a syncopated substitution between form, color and infinite with the whole resembling nothing and then much equally piece of sheet music.

Jean Tinguely, Fragment from Homage to New York (1960)

While Jean Tinguely was a signatory of the manifesto establishing Nouveau Réalisme (France's equivalent to Pop Art), the Swiss artist's piece of work was really more Dadaist in spirit. He was known for kinetic sculptures designed to autodestruct in pyrotechnic performances—the almost famous being Homage to New York, staged in MoMA's sculpture garden in 1960. This remnant is all that'south left of an event that, in retrospect, seemed to accept ready the tone for the explosive decade to come.

Barnett Newman, Broken Obelisk (1963–69)

Newman's place in art history rests on his reputation every bit the painter of sublime, color-field compositions divided by vertical lines he called "zips." But he likewise made sculptures, and this monumental work, which in the past has occupied pride of place in MoMA's atrium, is perhaps his all-time known. Two forms taken from Ancient Egyptian architecture—the obelisk and pyramid—are counterbalanced noon to noon, with the column of the former appearing to have been snapped in half, leaving just the upper portion to assume its unstable perch. Unlike readings of Cleaved Obelisk accept been proposed, with some critics opining that it's consistent with the transcendent aims of Newman paintings like, Vir Heroicus Sublimis, while others cite the shattered column equally evidence of an antiwar statement.

Andy Warhol, Brillo Box (Lather Pads) (1964)

The Brillo Box is peradventure the best known of a series of sculptural works Warhol created in the mid-'60s, which effectively took his investigation of pop culture into 3 dimensions. True to the proper name Warhol had given his studio—the Mill—the artist hired carpenters to work a kind of assembly line, nailing together wooden boxes in the shape of cartons for various products, including Heinz Ketchup, Kellogg's Corn Flakes and Campbell's Soup, as well Brillo soap pads. He then painted each the colour matching the original box (white in the case of Brillo) before adding the production name and logo in silkscreen. Created in multiples, the boxes were often shown in large stacks, effectively turning whatever gallery they were in into a high-cultural facsimile of a warehouse. Their shape and serial product was perhaps a nod to—or parody of—the then-nascent Minimalist mode. But the real point of Brillo Box is how its shut approximation to the existent thing subverts the conventional view of fine art, by implying that at that place's no real difference between manufactured goods and piece of work from an artist's studio.

Donald Judd, Untitled (Stack) (1967)

Donald Judd'south name is synonymous with Minimal Art, the mid-'60s motility that distilled modernism'south rationalist strain to blank essentials. For Judd, sculpture meant articulating the work's concrete presence in space. This idea was described by the term, "specific object," and while other Minimalists embraced it, Judd arguably gave the idea its purest expression by adopting the box every bit his signature form. Like Warhol, he produced them every bit repeating units, using materials and methods borrowed from industrial fabrication. Different Warhol's soup cans and Marilyns, Judd'south art referred to nothing outside of itself. His "stacks," are among his best-known pieces. Each consists of a group of identical shallow boxes made of galvanized sheet metallic, jutting from the wall to create a column of evenly spaced elements. Just Judd, who started out as a painter, was simply as interested in color and texture every bit he was in grade, as seen here past green-tinted car-body lacquer applied to the front face of each box. Judd'south interplay of colour and cloth gives Untitled (Stack) a fastidious elegance that softens its abstract absolutism.

Dan Flavin, untitled (to the "innovator" of Wheeling Peachblow) (1968)

Dan Flavin's lite sculptures are considered prime number examples of Minimalism, though he rejected the term for his work. This makes sense when you consider his diverse configurations of fluorescent color fixtures hateful little as concrete objects. The lite they emit is the main attraction, so in more means than i, they only piece of work when turned on. Still, in true Minimalist fashion, Flavin's works are made to relate to their environs in a matter-of-fact fashion. Flavin even refuted any sublime or transcendent associations with light. They are but a materials, in his view, the product of items that could exist found in any hardware store. This piece is a proficient example of how he married the compages of a room to his piece of work—in this instance, past using a corner to create a cage of color formed by outwardly and inwardly directed fixtures. Though the latter bring together together as a sort of frame or threshold, they are secondary to optical afterglow created by the piece'south mix of white and yellow light.

Richard Serra, Ane Ton Prop (House of Cards) (1969)

Following Judd and Flavin, a group of artists departed from Minimalism's aesthetic of make clean lines. As part of this Postminimalist generation, Richard Serra put the concept of the specific object on steroids, vastly enlarging its scale and weight, and making the laws of gravity integral to the idea. He created precarious balancing acts of steel or pb plates and pipes weighing in the tons, which had the effect of imparting a sense of menace to the work. (On two occasions, riggers installing Serra pieces were killed or maimed when the work accidentally collapsed.) In recent decades, Serra'south work has adopted a curvilinear refinement that's made it hugely popular, simply in the early going, works like One Ton Prop (House of Cards), which features four pb plates leaned together, communicated his concerns with brutal directness.

Lynda Benglis, Blatt (1969)

In a 1974 issue of Artforum, Benglis took out an advertisement in which she posed naked, belongings one end of a very long and lifelike dildo that protruded from her crotch. The prototype, a promotion for an upcoming exhibition, was the most infamous of a serial of ads and posters meant to ship-up Hollywood cheesecake and an fine art globe dominated by male artists. Though Benglis didn't think of the advertizement equally fine art per se, it became her signature endeavour. It was consistent with the sexual subtext, running throughout her piece of work, including this piece. 1 of a series of "pours," which puddled pools of latex in Solar day-Glo colors on the floor, Blatt's suggestion of abject bodily fluids is unmistakable, as is its recall of Pollock's "drip" paintings, with their own connotations of urination and ejaculation. As Blatt shows, Benglis's feminist critique is commonly couched in explorations of course and color.

Eva Hesse, Repetition Nineteen III (1968)

Like Benglis, Hesse was another woman artist who filtered Postminimalism through an arguably feminist prism. A Jew who fled Nazi Germany every bit a kid, she explored organic forms, creating pieces in industrial fiberglass, latex and rope that evoked skin or flesh, genitals and other parts of the body. Her works often consist of multiple elements, similar the ones in Repetition Xix III, though they aren't verbal duplicates of each other. Given her background, information technology's tempting to find an undercurrent of trauma or feet in her art—more obviously so, perhaps, in the paintings that preceded her sculptures. They reveal Hesse'southward roots in German language and Abstract Expressionism, also equally Surrealism, and speak to buried feelings of destruction and despair.

Claes Oldenburg, Geometric Mouse, Scale A (1975)

Oldenburg is considered a pioneer of '60s Popular Art, but his oeuvre never entirely fit the genre. While Lichtenstein, Rosenquist and Warhol borrowed cultural signs such as cartoons, Tinseltown icons and billboards, Oldenburg directed his attention to everyday items—appliances, household fixtures, types of food and the like. He played with scale (enlarging a hamburger to awe-inspiring proportions) and qualities of hard and soft (transforming a similarly blown-upwardly bathroom sink into sagging, flaccid mass of sewn vinyl) in means that were simply as Surreal equally they were Popular. The image backside Geometric Mouse, all the same, is a bit closer to pure Popular Art in that information technology's a comic-book-style outline of a rodent's head—one that seems to recall Disney's Mickey. This image crops up in number of Oldenburg'south works, forming, in 1 case, the overall configuration of his Mouse Museum, a taxonomic display of the creative person'south sculptural maquettes housed in a walk-in construction congenital of plywood and corrugated aluminum. In this outdoor sculpture, Oldendburg bends the mouse'due south features into system of planner forms, creating a humorous take on a formula used in sculptures by abstractionists, like Anthony Caro.

Justen Ladda, Tide (1985)

A native of Frg, Ladda was part of a postmodern wave of artists emerging in New York during the late 1970s and early 1980s, a period in which various revivals of Pop Art, Expressionism and Minimal Art combined to further collapse the boundary between high and low culture. While Ladda'due south work came out of this ferment, it was e'er hard to categorize. His specialty is a kind of site-specific trompe l'oeil, the best-known example of which is a wall landscape of the Curiosity comic-volume antihero, the Thing, created in an abandoned Bronx pic theater. From a certain angle, the figure, seen charging at the viewer, appears to leap from two-dimensions into three, thanks to a perspectival trick in which the Thing'due south forward-planted leg and shadow are painted beyond the summit of the seats in front end of the epitome. Tide employs like legerdemain, this time past superimposing Albrecht Dürer'south 1508 drawing, Praying Hands, on scores of detergent boxes layered in a crude, cubistic approximation of the subject area. Different parts of the image, including the original's blue background, are painted in repeating patterns on dissimilar sides of the boxes to create an uncanny appropriation of Dürer's masterpiece when viewed from a certain angle. A quick shift to the side, however, reveals orange packaging emerging from the blueish, shattering Ladda's deception. Out of this clash of color and dimensions, Ladda sets upward a similar confrontation between the sacred and profane and betwixt religious symbol and brand.

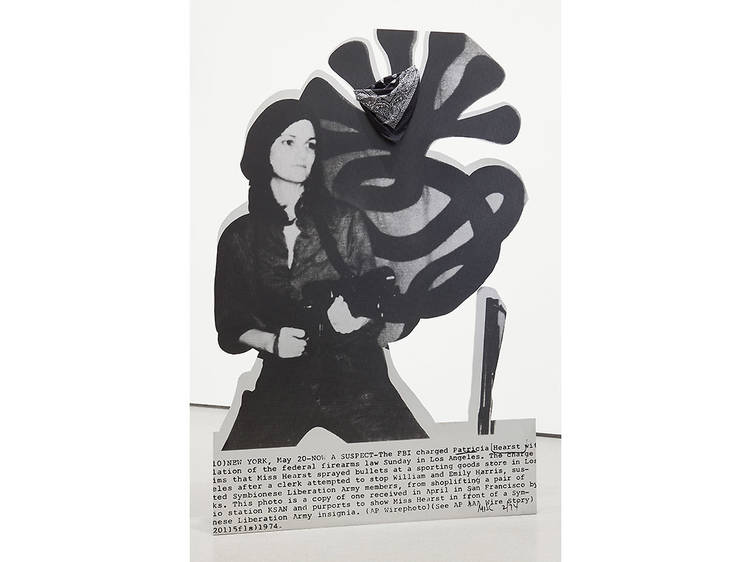

Cady Noland, Tanya equally Bandit (1989)

Before she largely quit exhibiting, Noland, whose father was renowned color-field painter Ken Noland, enjoyed a run of success in the belatedly 1980s with works that laid bare the fallacy of the American Dream, the cocky-mythologizing of the Reagan Era and the endemic violence of American guild. The disharmonize between police force and liberty, and the way outlaws are celebrated as the purest embodiments of the pursuit of happiness are themes that run though works consisting of steel pipes, chain-link fencing, handcuffs, beer cans and American flags, every bit well equally enlarged paper photos of notorious public figures silkscreened onto big aluminum panels. This piece centers around i such image of Patty Hearst, the publishing heiress whose 1974 abduction by a left-wing terrorist prison cell calling itself the Symbioses Liberation Army caused a media awareness—especially when, in the course of her 19-calendar month captivity, she appeared to willingly renounce her former life and join the group equally Tanya. Hither, Noland employs the iconic epitome of Hearst-as-Tanya, capped in a beret and brandishing a rifle while posed in forepart of the SLA flag featuring the emblem of a seven-headed cobra snake. Hearst and the ophidian are in cutout, with the original wire-photo caption anchoring the piece like the base of a sculpture. A bandana is hung to the right above Tanya'due south head, as if waiting to for someone to don it for a heist. Its meaning is unmistakable, simply the more nuanced message here is that the American promise of personal agency and reinvention causes collateral impairment.

David Hammons, African-American Flag (1990)

Amidst artists of color exploring the issue of identity, Hammons is notable considering his work emphasizes the American aspect of the African-American experience. He doesn't simply indict racism and the country'southward racist by, though at that place is some of that. Instead, his work evokes how blackness people and black culture are bound inseparably to the history of the United States and vice versa. This transformation of the cherry-red, white and blue into the dark-green, blackness and red of the Pan-African flag could be taken equally an ironic human activity, but it also encapsulates the codependent graphic symbol of black/white relations.

Mike Kelley, Untitled (1990)

Mike Kelley'due south provocative and multilayered output comments upon and critiques numerous facets of contemporary life, including pop culture, sex activity, religion and the persistence of class in a supposedly classless society. Although Kelley (1954–2012) was an internationally recognized fixture of the Los Angeles fine art scene, the energy and acrimony in his work ultimately drew upon his Irish-Catholic upbringing as the son of a janitor in Detroit—only equally the city embarked on its half-century turn down as an industrial powerhouse. This 1990 piece is part of a serial of works begun in the late 1980s that incorporate plush toys and crotched items culled from austerity stores. Kelley insisted this piece and the others like it were never intended as ironic evocations of nostalgia or depression-culture tastes; instead, he described them as formal exercises. Certainly Untitled could be viewed as a classic figure/ground study with its yarn dolls placed atop Afghans that lucifer their form, color and texture. More to the signal, its arrangement on the floor recalls the work of Minimalists similar Carl Andre. Notwithstanding, an undeniable aroma of desolation clings to Untitled, equally if to suggest a life abandoned because of straightened circumstances.

Charles Ray, Family Romance (1993)

Ray'due south work could exist described as a Postconceptual foray into trompe fifty'oeil, though not necessarily in the usual sense of making something look existent when it isn't. His interests lay in provoking a perceptual double accept past using shifts in course and fabric to produce uncanny effects. Case in point is Family Romance, which takes its title from Freud'south study of sublimated erotic desires between family members. Here, Charles creates his ain version of a nuclear family with a mannequin-like father and mother, sis and brother, standing before the viewer in a line while belongings hands. They're naked, and anatomically right with the difference between adult and child marked past the absenteeism or presence of public hair—a distinguishing factor that'southward peculiarly helpful given each family fellow member family is sized at the same top and body mass. Agonizing and destabilizing, the piece presents its Freudian theme as a metaphorical department store brandish of dysfunction.

Martin Kippenberger, Martin, Into the Corner, Yous Should Exist Ashamed of Yourself (1992)

Rambunctious, egotistical and a biggy drinker, Martin Kippenberger (1953–1997) intertwined life and fine art, creating a wide-ranging and prolific output that encompassed painting, sculpture, performance, photography—likewise as his own bad self. The force of his personality was arguably the primal ingredient property together a sometimes maddeningly uneven oeuvre. Kippenberger'south stated aim was to radically question the office of the artist in society, but information technology's probably fairer to say that he keenly felt the constraints of trying to brand important fine art in the late the 20th century. He understood, perhaps, that the revolutionary stance of early-modern artists had devolved past the time of his ain generation into bad-boy posturing. That could be ane subtext of this life-size cocky-portrait as a penitent schoolboy, ane of six differing versions created as a reaction to a German art critic'due south viciously negative review of his work. It is the perfect analogy of Kippenberger view of his art as an e'er-widening bicycle of provocation, with no existent aim other than effrontery itself.

Katharina Fritsch, Grouping of Figures (2006–xi)

Fritsch'southward works have the odd effect of making iii-dimensional objects seem flat: firstly, by borrowing her subjects from found sculpture (religious bronze being a frequent source), and secondly, by roofing each in a single color, which gives her pieces eerily muted presence, as if they'd been sprayed with a safe coating. The results seem more like copies of things than things themselves, devoid of the spirit of whatever original Fritsch based the piece of work upon. Her pieces are inanimate in every believable style, which simply adds to their spooky attraction. A good case is Grouping of Figures, an odd ensemble of saints and madonnas, standing level with the viewer. Their ranks take been joined past a fairytale giant, leaning on his order, a sinuous snake and three forms on alpine pedestals, including a truncated classical female nude, an urn and a pair of skeleton feet. What they mean lonely or together is difficult to say, though Fritsch has immune that sure biographical details are referenced: The nude is borrowed from one that occupied the garden of her childhood home, while the skeleton parts recall her childhood memory of the onetime 10-ray fluoroscopes used in children's shore stores during the 1950s to measure out anxiety. Yet, while Group of Figures may take links to the creative person's past, they appeared tuckered of any associations with memory—or annihilation else for that matter. Taken together, Fritsch'south tableaux recalls the aftermath of a night at the museum, where objects managed to current of air up in the wrong place without coming alive.

Rachel Harrison, Alexander the Great (2007)

Harrison's piece of work combines ceremonial with a knack for infusing seemingly abstract elements with multiple meanings, including sociopolitical ones. While her efforts include forays into painting, drawing, video and photography, she'south above all a sculptor who questions her medium, particularly its historical association with monuments and their celebrations of masculine power. Alexander the Not bad is an energetic send-up of that idea, with its caped (if otherwise naked), mannequin standing in for the Macedonian general who conquered the world. But more than that, the piece evokes all of the great-man figures immortalized in statuary or rock—as Harrison suggests past her inclusion of an Abe Lincoln mask covering the dorsum of the dummy'south caput. (In a groovy detail, the rail-splitter'south visage is fixed in identify past sunglasses worn astern past the host, a sartorial arrayal normally embraced past fratboys, surfer dudes and other species of bro who imbue male privilege with a casual-Friday air.) Alexander/Abe poses astride a large, elongated, boulderlike base of operations, splotched in bright-colors like ejecta from an evil-clown volcano. At the same time, he grasps a large bucket or waste-can decorated with a NASCAR racer. All of these signifiers of manliness are subverted by the figure'south androgynous combination of a female caput plunked on the trunk of a pre-pubescent male child or girl. Harrison creates a disconnect between Alexander'south triumphal carriage (the rock is reminiscent of a Pharaoh'south bark gliding along the Nile, or a promontory overlooking a battlefield) and his childlike course.

An electronic mail yous'll actually love

🙌 Awesome, you're subscribed!

Thank you for subscribing! Look out for your get-go newsletter in your inbox before long!

Source: https://www.timeout.com/newyork/art/check-out-the-top-25-sculptures-at-moma

0 Response to "Picture of the Statue of Liberty Picture of the Museum of Modern Art in New York"

Postar um comentário