The 120 Days of Sodom Read Online

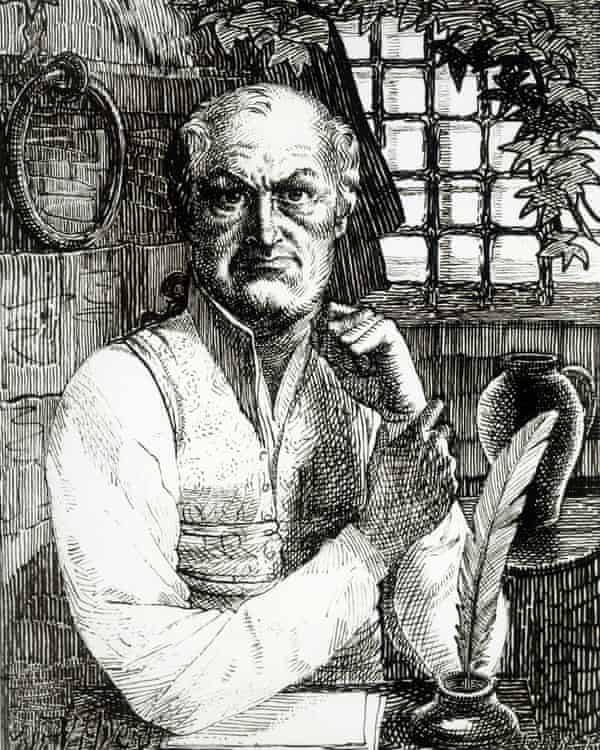

O north 3 July 1789, in the middle of the night, the Marquis de Sade was dragged from his jail cell in the ironically named Liberty belfry of the Bastille. Earlier that twenty-four hour period he had been caught shouting to the crowd gathered exterior the prison walls that the inmates' throats were being cut. He was transferred to an asylum outside Paris, and forced to exit many of his about precious possessions behind, including a copper cylinder kept hidden in a crevice in the wall. When his wife set off for the Bastille to fetch his holding on 14 July, information technology was already too belatedly: the Revolution had beaten her to it, and she had to turn back empty-handed.

Sade wept "tears of blood" over the loss. Inside the cylinder was a ringlet, 12m long and 11cm wide, covered in minute handwriting: the manuscript of an unfinished novel called The 120 Days of Sodom, or The School of Libertinage.

Though Sade never saw his scroll once again, its story was far from over. Somehow it escaped the storming of the Bastille in the hands of a swain called Arnoux de Saint-Maximin, who then sold it to a Provençal aristocrat, the Marquis de Villeneuve-Trans. His family unit held on to it for more a 100 years earlier eventually selling it to a German collector, who allowed the pioneering sexologist Iwan Bloch to publish the novel for the first time in 1904. Sade's descendants, the Nouailles family, bought the scroll back in 1929 and kept information technology until 1982, when they entrusted the publisher, Jean Grouet, with its valuation. Simply he smuggled it over the edge to Switzerland, and sold it to a leading collector of erotica, Gérard Nordmann. Decades of legal wrangling ensued between the Nouailles and the Nordmanns, only resolved in 2014 when a private foundation acquired the scroll for €7m and placed it on display in Paris. The exhibition was cut short when the director of the foundation was charged with fraud. The curlicue, which started its life in prison, is thus under lock and key once again, waiting for the courts to decide its future.

The story of the scroll, complete with Provençal noblemen, prison house-breaks, and shadowy booksellers, reads rather like the life of the man who created information technology. By the time Sade wrote The 120 Days he had spent viii years in prison, first in Vincennes then the Guardhouse. He had likewise been shot at, burnt in figure and forced to live on the run – on 1 occasion escaping to Italia with his sis-in-law, and lover, Anne-Prospère. Though the Surrealists would eventually cast him as a martyr to liberty, Sade was in prison not for his words but for his deeds. He was a notorious libertine even by the standards of his age. His 20s and 30s had been marked past a serial of public scandals: a sexual attack on a young woman named Rose Keller; an orgy in Marseille which led to four prostitutes falling sick after consuming chocolate-coated Spanish fly (an aphrodisiac); and, about disturbingly, a winter spent in his chateau with his married woman and several freshly recruited servants aged around fifteen – the so-called "little girls affair". Afterwards years of covering up her son-in-law'southward behaviour, Madame de Montreuil had finally had enough: she had the rex sign a lettre de cachet, a imperial warrant that meant Sade could be incarcerated indefinitely. He was arrested in February 1777 and remained in prison for the side by side 13 years.

Sade began drafting his novel in earnest on 22 October 1785, working from vii to ten each evening over 37 sequent days. The novel is non consummate, however, every bit only the introduction and the commencement of its four parts are written in total. The residuum are very detailed summaries merely no more. Though he had ample opportunity over the next iv years, Sade never completed his first – and most farthermost – novelistic enterprise. Perhaps he realised it was unpublishable – a decision that censors and courts around the globe would repeatedly endorse over the course of the 20th century. He described his novel as "the near impure tale ever written since the world began" and, for all the hyperbole, his description even so holds true even now.

The 120 Days tells the tale of four libertines – a knuckles, a bishop, a estimate and a broker – who lock themselves away in a castle in the Black Wood with an entourage that includes 2 harems of teenage boys and girls specially abducted for the occasion. Four ageing brothel madams are appointed as storytellers for each of the four months, and their brief is to weave a 150 "passions" or perversions into the story of their lives.

The libertines, surrounded by their victims, listen and enact the passions described, and as the passions go more vicious, so do the libertines: the novel builds to a trigger-happy climax with the "criminal" and "murderous" passions of Parts Three and Iv. These are presented equally long, numbered lists, interspersed with cursory accounts of the scenes they inspire. Sade's tortures range from the cartoonish ("He vigorously flattens a pes with a hammer") to the clinical ("Her air supply is turned off and on at whim inside a pneumatic machine"); and from the surreal ("They make her swallow a ophidian which in turn will devour her") to the mundane ("He dislocates a wrist"). But the vast majority are simply too obscene and too violent to be quoted, as one nameless victim afterward some other is subjected to increasingly elaborate and frenzied torments.

These relentless lists read similar a series of nightmarish diary entries, or a set of instructions for an apprentice torturer. The 120 Days is non a work that seduces its readers: it assaults them. Reading it is, thankfully perhaps, a unique experience.

Sade'southward once unpublishable novel has now joined the ranks of Penguin'due south Classics for the first fourth dimension, and its author will take his identify alongside the neat figures of world literature – many of whom would no dubiety turn in their graves at the news that their gild now counted Sade among its members. It is a significant cultural moment for a work that was for and then long the preserve of a privileged few. Indeed, ever since Sade began piece of work on his typhoon, The 120 Days has been a hidden text – subconscious start by its author and later past its subsequent owners.

For much of the 20th century, fifty-fifty those who published the novel did their all-time to keep it away from the prying optics of the authorities. These early editions were published – pseudonymously or anonymously in some cases – in very small numbers for private and wealthy subscribers, and thus remained inaccessible to the full general public. Information technology is no coincidence that Jean-Jacques Pauvert – the first publisher to put his own proper noun to an edition of Sade'southward major works, and the first to attempt a larger print run – was prosecuted by the French government in 1956 for committing an outrage against public morals.

Pauvert argued that Sade'south works were "doc-legal documents" of groovy scientific value, and that his editions were in whatever case besides expensive for ordinary members of the public to buy. Most of his sales, he insisted, had been to doctors and medical faculties – Sade was, in other words, in safe hands. The judge disagreed, merely his verdict was overturned on appeal, and a lilliputian over a decade later, Sade'southward works were bachelor in France in mass-market paperbacks. Sade is now firmly established as part of the French literary canon.

This business organization virtually the wider circulation of the works was as revealing of class anxieties every bit it was most attitudes towards Sade. To say that his works posed a take a chance to the public was really to say that a public able to read Sade was itself a risky prospect. These aforementioned anxieties resurfaced a few years afterward across the Channel, merely when it looked every bit if Sade was get-go to gain a foothold in British civilisation.

Though the translations published by the Olympia Printing in Paris were banned from the UK throughout the 1950s, British publishers such as Peter Owen were able to produce (very careful) selections from Sade'south writings without running into problem. In the wake of the Lady Chatterley's Lover trial in 1960, a exam case for the Obscene Publications Act passed a twelvemonth before, more than publishing houses were emboldened to publish Sade. But all this came to a halt with the Moors murders trial of 1966, and with the revelation that Ian Brady had endemic a paperback Corgi edition of Sade'due south Justine.

Brady'south taste in books was widely reported in the tabloid press, and fired the public imagination – a burn down stoked past commentators who saw his reading of Sade in "fairly contempo paperback" and his crimes as a matter of cause and upshot. George Steiner alluded to the "high probability" that Brady's reading of Justine was a "significant gene" in the example. Pamela Hansford Johnson fretted near the threat posed by the rise of "a semi-literate reading public": "There are some books that are non fit for all people and some people who are not fit for all books."

It did not seem to affair that the copy of Justine that Brady owned had only appeared in print after he had committed all but one of his murders. A ban on the publication and importation of Sade'due south works swiftly followed the trial and remained in consequence for more than 20 years. When a British publisher, Arrow Books, finally tested the ban by reprinting Sade'southward major novels in the late 1980s and early 90s, Ann Winterton MP led calls for the DPP to act, condemning Juliette as "filth of a particularly ugly and dangerous kind".

Information technology is hard to imagine a work of fiction prompting calls for prosecution in Britain today. The written word no longer seems to frighten people in the aforementioned way any more. The fright that novels used to inspire has shifted instead to more contempo – and visual – forms of fiction and fantasy such as video games, horror movies, and net pornography.

Information technology is telling that the controversial section relating to "extreme pornography" in the Criminal Justice and Immigration Human activity 2009 deals only with images, and makes no mention of the written word. But is this because words now seem prophylactic, or because they are just as well slippery for the law?

In 2003, MPs debated whether "paedophile pornography" could exist textual too every bit visual. A young George Osborne advised his swain MPS against delving into the "quagmire" of words: "In previous generations, people have been dragged into debates about works of literature, such as Lolita, or works that practice non quite qualify equally literature, such as those by the Marquis de Sade, and parliament should non exist fatigued downwards that avenue once again." Even works that are "not quite" literature have words in them – reason enough, Osborne suggests, for politicians and lawyers to steer clear of them.

Practice Sade'southward novels now qualify as smashing literature? That a novel every bit extreme as The 120 Days is office of a "classics" collection tells u.s. just how much our sense of literature has changed over the by few decades. And publishing The 120 Days equally a classic changes it still farther: if it makes Sade a little more than respectable, it also makes literature a footling more unsafe than it was before.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/oct/07/marquis-de-sade-120-days-of-sodom-published-classic

0 Response to "The 120 Days of Sodom Read Online"

Postar um comentário